While art historical discourse around the minimalist sculptor and printmaker Kim Lim was largely overlooked throughout her life, the artist and her works garnered much posthumous attention.

Major shows such as retrospectives presented by Tate Britain and STPI – Creative Workshop & Gallery here in Singapore took place almost two decades after her death, in attempts to re-contextualise her works and transnational identity. In the run-up to our second edition of The Singapore Art Supper Club focused on Kim Lim, in collaboration with Straits Clan and STPI, we wish to draw attention to the complexity and significance of her life and practice despite her late addition to the annals of art history.

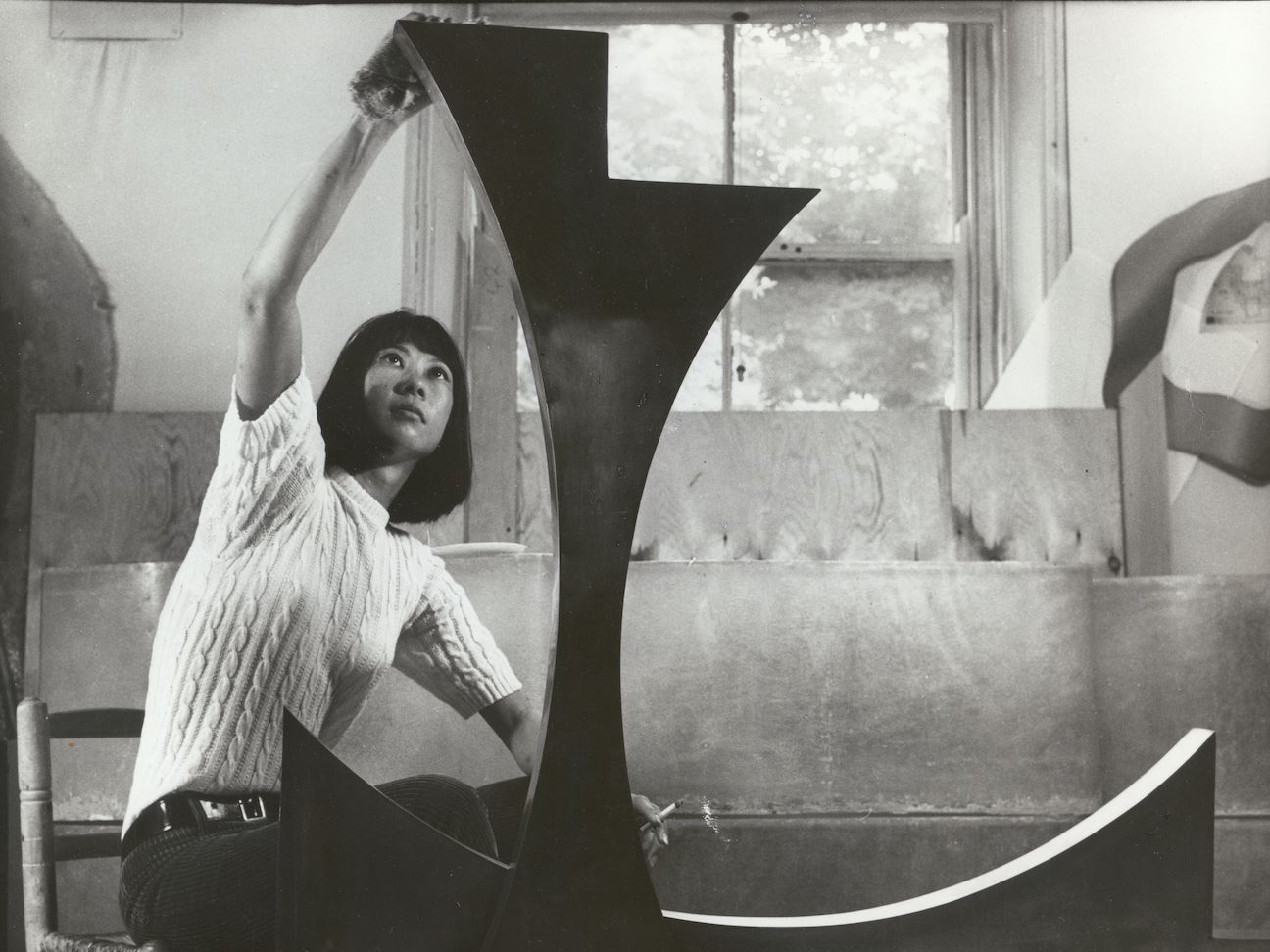

Kim Lim, ‘Twice’, 1966. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim.

1. Her practice was largely inspired by her cosmopolitan lifestyle.

Lim grew up in Singapore, Penang, and Malacca. She then moved to London to attend Saint Martin’s School of Art and Slade School of Art, concentrating on wood-carving and printmaking respectively. Pursuing her artistic career in the UK, and specifically being taught by the renowned British sculptor Anthony Caro, yielded much experimentation with materials like fibreglass, steel, and bronze. At the same time, Lim also looked to the Taoist principle wu wei, which can broadly be described as surrendering to the ebbs and flows of nature and life. Beyond this culmination of Eastern and Western influences, she was an avid traveller and made sure to visit places like Greece and Japan to seek inspiration from earlier civilisations. It is in this holistic approach of taking these different trajectories as a larger frame of reference that we are able to see thoughtful and rhythmic forms emerge in alignment with the visual language usually associated with the cosmos.

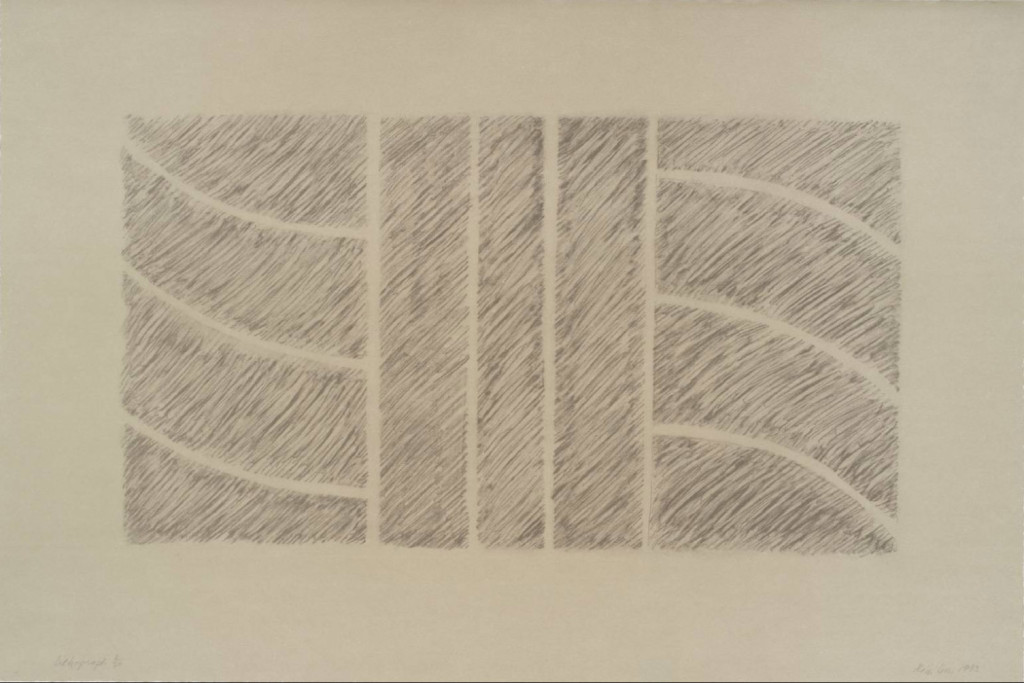

Kim Lim, ‘Ring’, intaglio print on paper, 1970. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim.

2. She took control of her positioning as an artist by rejecting an invitation to exhibit in a show that would portray her as ‘Other’.

There was a major group show in 1989 at the Hayward Gallery in London titled ‘The Other Story’ that brought together the works of Afro-Asian artists in post-war Britain, in which Lim politely declined to participate. She was vocal about how she wanted and did not want to be perceived or framed as. Her gender and race was often brought to the forefront in the way that she was contextualised and included in major institutional narratives. Whilst she acknowledges that her gender and race perhaps comes out in her work, she chose to not reinforce those tropes; instead, she spoke from an indeterminate place that was neither East nor West.

Kim Lim, ‘Pegasus’, Bronze, 1962. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim.

3. Her works were consistently and substantially collected throughout her life, but she still remained relatively obscured within art historical narratives.

It became clear to her that being a part of public collections did not guarantee inclusion in art history. Because of this, many of Lim’s major shows have become processes to re-examine the contexts that the artist was framed against in these past institutional approaches, to reposition former narratives with a new and more critical lens.

Kim Lim, ‘Waterpiece’, 1979. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim. Photo credit: Government Art Collection.

4. Her printmaking and sculptural practice ran parallel and complementary to one another.

Lim treated both mediums similarly in her exploration of space, rhythm, form, and light, embracing the nuances of whatever material she was working with. Appealing to the currents and rhythms found in nature, she rendered simple lines and repeated patterns that were endlessly in motion, yet controlled. Her sculptures, too, paid attention to the subtleties of texture and curves. It is from this distinct method that the duality within Lim’s practice emerges.

Kim Lim, ‘Trace II’, limestone, 1982. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim and Art UK.

Kim Lim, ‘Relief’, lithograph on paper, 1993. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim.

5. Her artistic journey is an important example that sheds light on how we read and write art history.

Lim has drawn attention to how narratives fluctuate and the importance of questioning factors seen as ‘givens’ in constructing certain frameworks. We celebrate her legacy not by focusing on her diaspora, her gender, or in relation to her white, male counterparts, but for her skilful, dexterous and evocative approach alone. It is this aesthetic Lim developed that led her to become one of the most prominent sculptors of her time.

Kim Lim, ‘Dua Huang’, lithograph on paper, 1988. Image courtesy of the Estate of Kim Lim.

Register here for the upcoming edition of The Singapore Art Supper Club: Kim Lim on 11 May or for a private viewing of Kim Lim’s works, on display from 5—23 May at Straits Clan.